By Lynette Morgan

At GRRAND, we believe in building community through deep and sometimes uncomfortable conversations — not just about science, but about who gets to belong, how knowledge is shared, and what it means to show up for one another.

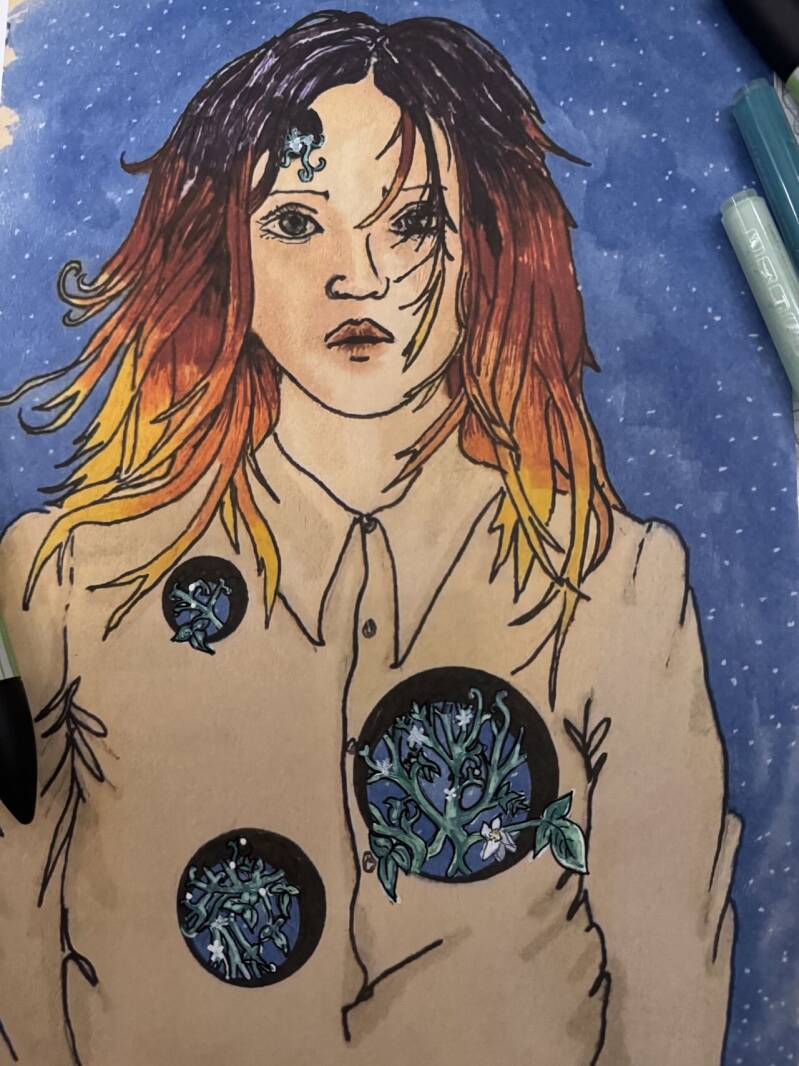

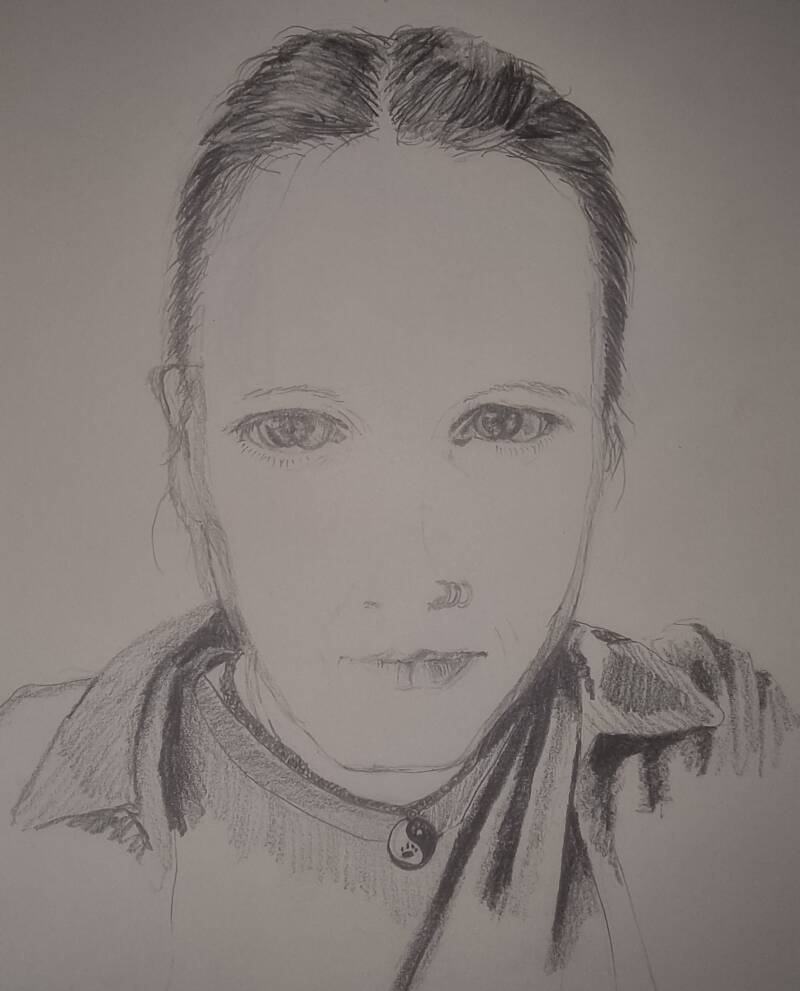

Our team is a neurodiverse and interdisciplinary collective: researchers, scientist-practitioners, clinicians, advocates, artists, service users, and lived experience educators. Together, we hold space to think, get it right, get it wrong, reflect, repair, and keep going.

That’s what makes this blog special: it is not simply one person’s voice, but a sample of the parallel processes we hold together — conversations that weave trauma and science, academic rigor and emotional truth, policy and poetry.

Every now and then we share with each other powerful personal reflections in our online exchanges on trauma, masking, and rediscovering identity after years of social survival. We share, this is why co-design, compassion, and community reflexivity matter — and why we don’t believe in “representing” people, but in creating with them.

To Belong or Not to Belong: A Context of Trauma

At the age of 46, my existential sense of self imploded.

I had been coordinating, with executive precision, multiple roles: senior neonatal nurse, lecturer, carer, and parent. But a series of traumatic events upturned my life and exposed the "real" me — the me beneath the mask. I was left with a translucent, vulnerable version of myself, no longer protected by the pseudo-identities tied to these roles. It was a version of me that was dissipated and without belonging.

Lifelong Invalidation: How It Starts and Persists

For many autistic people, trauma doesn’t always look like a single catastrophic event. Instead, it may be a slow accumulation of stress — social rejection, sensory invalidation, chronic misunderstanding. These experiences alter us not just emotionally, but neurologically. Our brains are wired through lived experience.

When my car overheated and broke down, I didn’t just experience inconvenience. I was flooded with a cascade of helplessness — not just from that moment, but from a neural portal to every other moment where I had felt trapped, blamed, unseen. Workplace bullying. Microaggressions. Lifelong gaslighting. My trauma didn’t “make sense” to others, because it wasn’t about the car. It was about self-worth.

And because of how autistic sensory-emotional processing works — like the single synapse between the olfactory system and the amygdala — I felt it all at once. Trauma is not always what threatens your life. Sometimes, it’s what threatens your freedom to exist as you are.

Losing Identity: A Survival Mechanism

Our brains are social organs. We are wired for kinship, reciprocity, recognition. What happens when those things are denied? When you are chronically othered — or when you cannot see yourself in anyone around you?

You lose yourself, just to survive.

Masking and the Divided Self

Masking was my armour. At first. But over time, it warped me. I shaped myself into whatever would be accepted. I worked, I smiled, I complied. But I didn’t belong.

The dissonance was unbearable. People once labelled autistic people as “fantasists.” But what if the fantasy was not ours, but the persona we were forced to create just to function?

Eventually, I cracked. And beneath the roles and resilience and regulation, I found rage. Grief. Injustice. And an absence of self-worth so complete, I no longer recognised myself.

“For me it was an insidious symbiotic armour of masking, which had contorted, morphed, disfigured, and scarred my core sense of self. Masking causes an existence of cognitive dissonance and divided identity. There is nothing quite akin to this fake reality, autistic people were once described as fantasists. But I wonder how much of this is a behaviouralist’s perspective of masking. Somewhat ironically the etymology of the word autism – suggests it’s a state of being ‘oneself’.

I found that I had dissociated and was fawning and masking to fill spaces that were left by trauma. As well as appropriating myself to cultural norms I had no clear boundaries and had suffered abuse and bullying unknowingly. At the time of my life imploding- this reality hit me, along with burgeoning feelings of injustice from gas lit unmet needs. All consolidated by suffocation of a sense of identity. Without identity there was no sense of worth or esteem. The internalised rhetoric was ableist, self-deprecating and coercive. “

From Void to Realisation

When the mask came off — or shattered — I sat with the fragments. I started to trace the roots of my dismembered identity. Slowly, I began to build something more real. The trauma didn’t disappear, but I began to name it. I stopped blaming myself. I began to understand that surviving systems that gaslight you is not failure — it’s resistance.

Finding Authenticity (and Protecting It)

I won’t pretend there’s a single method for healing. But for me, some things helped:

- Protection: Building self-understanding and compassion as the foundation of advocacy and boundaries.

- Processing: Letting go of internalised ableism and rewriting the harmful scripts I had carried for years.

- Prevention: Creating environments where I could enter monotropic flow, feel safe in my sensory body, and celebrate diversity without needing to explain it.

Why This Story Belongs in GRRAND

At GRRAND, we do not see stories like mine as “extra” or “emotional context.” They are data. They are expertise. And they are the reason we push for systemic change.

We don’t just review training materials — we co-design them.

We don’t just use neurodivergent voices — we build platforms for them.

We don’t just aim to get things right — we stay in dialogue when we get things wrong.

This is how belonging is made. Not through inclusion alone, but through co-creation and care.

It reflects the kind of learning, unlearning, and healing we strive to do together as a team.

Add comment

Comments